Pink Floyd - Rock & Folk

- Apr 12, 2022

- 8 min read

Publication date: March 2015

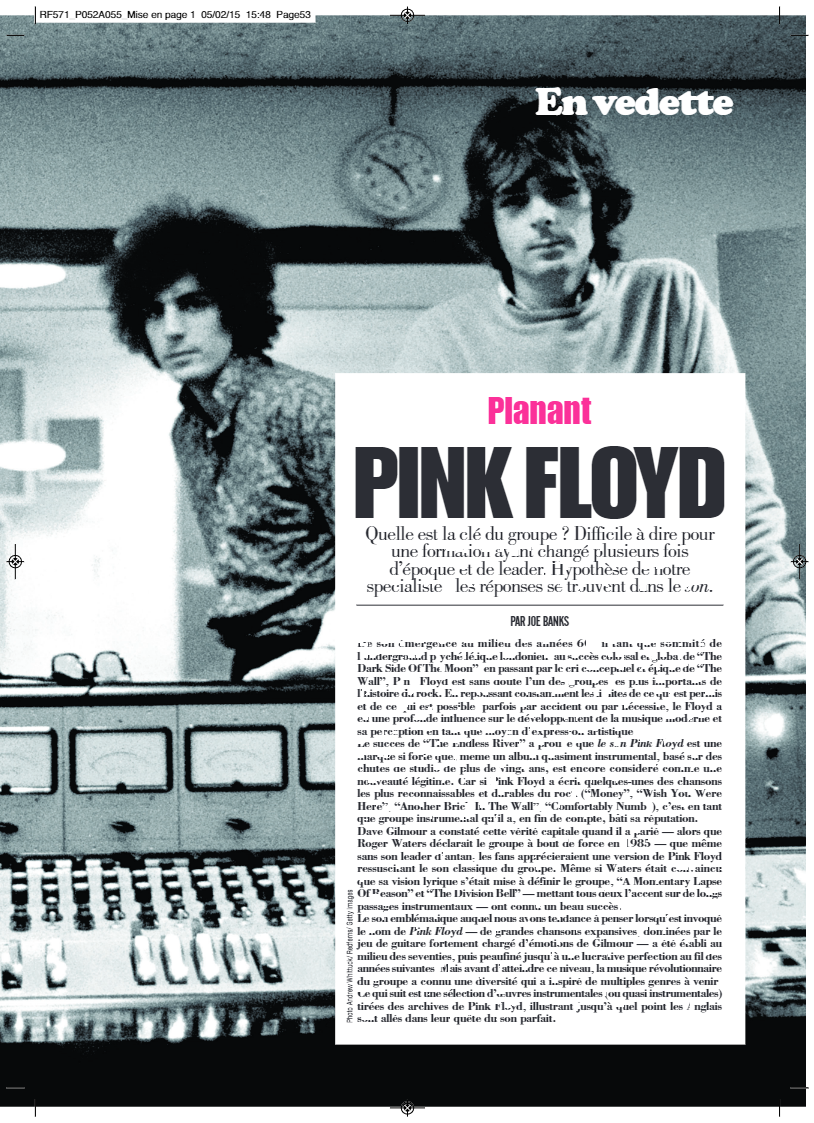

With Random Precision – Defining the Sound of Pink Floyd

From their emergence in the mid-60s as the leading light of London’s psychedelic underground, through the record-breaking global success of ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’, to the epic conceptual scream of ‘The Wall’, Pink Floyd are without doubt one of the most important bands in rock history. By constantly pushing at the boundaries of what’s permitted and what’s possible, sometimes by accident, sometimes by necessity, Floyd have had a profound influence on both the development of modern music and its perception as an art form.

The success of ‘The Endless River’ has shown ‘the Pink Floyd sound’ to be such a strong brand that even a mostly instrumental album based on studio outtakes from over 20 years ago can still be regarded as a legitimate release. Because while Floyd have written some of rock’s most recognisable and enduring songs – “Money”, “Wish You Were Here”, “Another Brick In The Wall pt 2”, “Comfortably Numb” etc – it’s as an instrumental unit that the band ultimately built their reputation.

This is an essential truth that Dave Gilmour realised when, despite Roger Waters declaring the band “a spent force” in 1985, he correctly gambled that, even without its erstwhile leader, a version of Pink Floyd that re-booted the ‘classic’ Floyd sound would find favour with the fans – and so it proved. Despite Waters’ belief that it was his lyrical vision that had come to define the band, both ‘A Momentary Lapse Of Reason’ and ‘The Division Bell’ – with their emphasis on long instrumental passages – were well-received in their own right.

The signature sound we tend to think of whenever the name ‘Pink Floyd’ is invoked – big, expansive songs dominated by Gilmour’s powerfully emotional guitar playing – was established in the mid-70s and then honed to lucrative perfection over the following years. But before reaching this point, the band created a diversity of ground-breaking music that provided inspiration for multiple genres to come. What follows is a selection of instrumental (or near instrumental) works from the Floyd archives that illustrate just how far out the band went in their pursuit of the perfect sound.

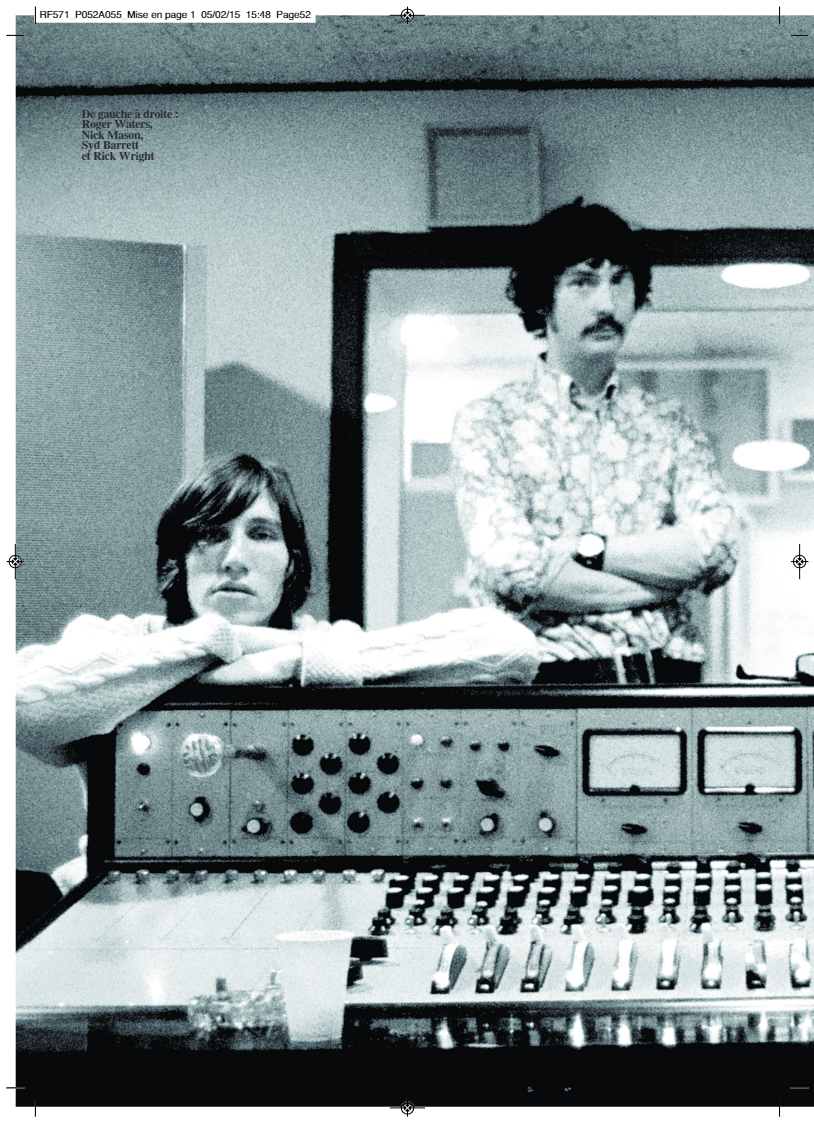

“Interstellar Overdrive” (from ‘The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn’, 1967)

While the band would often deny it in years to come, the genre they’re most commonly tagged as pioneering in their early days is space rock. In contrast to the bedazzled psych pop and groovy freakbeat on the rest of their debut album, the ten minute “Interstellar Overdrive” was far more representative of the synapse-blasting live shows they’d first come to attention with. Based around a harsh, churning riff, the song soon peels off into the void on the back of a trance-inducing bass line, Waters’ playing often acting as a simple melodic anchor in their early sonic explorations. Syd Barrett’s guitar clangs and chirrups away in the margins, with no pretence to conventional soloing, before a nebulous cloud of Rick Wright’s Farfisa organ approaches like the emissary of an alien race. Grinding and gnarly, and constantly on the verge of tripping over into abstract noise, this was defiantly not the soundtrack to the Age of Aquarius.

“A Saucerful Of Secrets” (from ‘A Saucerful Of Secrets’, 1968)

With Barrett forced out of the group due to his increasingly erratic behaviour, Floyd fell back on their ability to create lengthy, instrumental improvisations where avant-rock primitivism won out over jazz or blues-based virtuosity. Fittingly for a bunch of former architecture students, they mapped out the various sections of their second album’s title track on a diagrammatic chart and created a prototype of the epic, multi-part compositions to come. With its sinister droning fade-up and keening exploratory organ suggesting something vast looming into view, “A Saucerful Of Secrets” leaves the cranky propulsion of “Interstellar Overdrive” far behind in its implacable wake. There’s a sustained battery of heavy percussion – actually a drum loop created by Nick Mason – over which discordant piano and indecipherable guitar transmissions enact some cosmic battle. But as a mournful church organ and host of heavenly voices bear witness to the aftermath, the path to a more progressive future for Floyd starts to open up.

“Careful With That Axe, Eugene” (b-side to “Point Me At The Sky”, 1968 / ‘Ummagumma’, 1969)

If “A Saucerful Of Secrets” began to see the emergence of a more cerebral sound, “Careful With That Axe, Eugene” marks the band’s transition from acid abstraction to dope-fuelled meditation, from “crazy, man!” to “yeah, man…” Guitar and organ cascade and entwine over another simple see-sawing bass line, but they’re noticeably more purposeful and melodic than before. There’s a scream low in the mix, then Gilmour lets loose a trippy solo that’s already anticipating his distinctive sound and style. Overall, the whole band’s playing is tighter and more controlled, carrying the listener along rather than threatening to lose them in a haze of amorphous noise. The live version on ‘Ummagumma’ is even more dynamic, its longer, dreamier build-up suddenly giving way to a full-scale explosion of guitar and drums. It’s a viscerally exciting piece of sonic drama that would be copied frequently in years to come, and practically sets the template for post-rock.

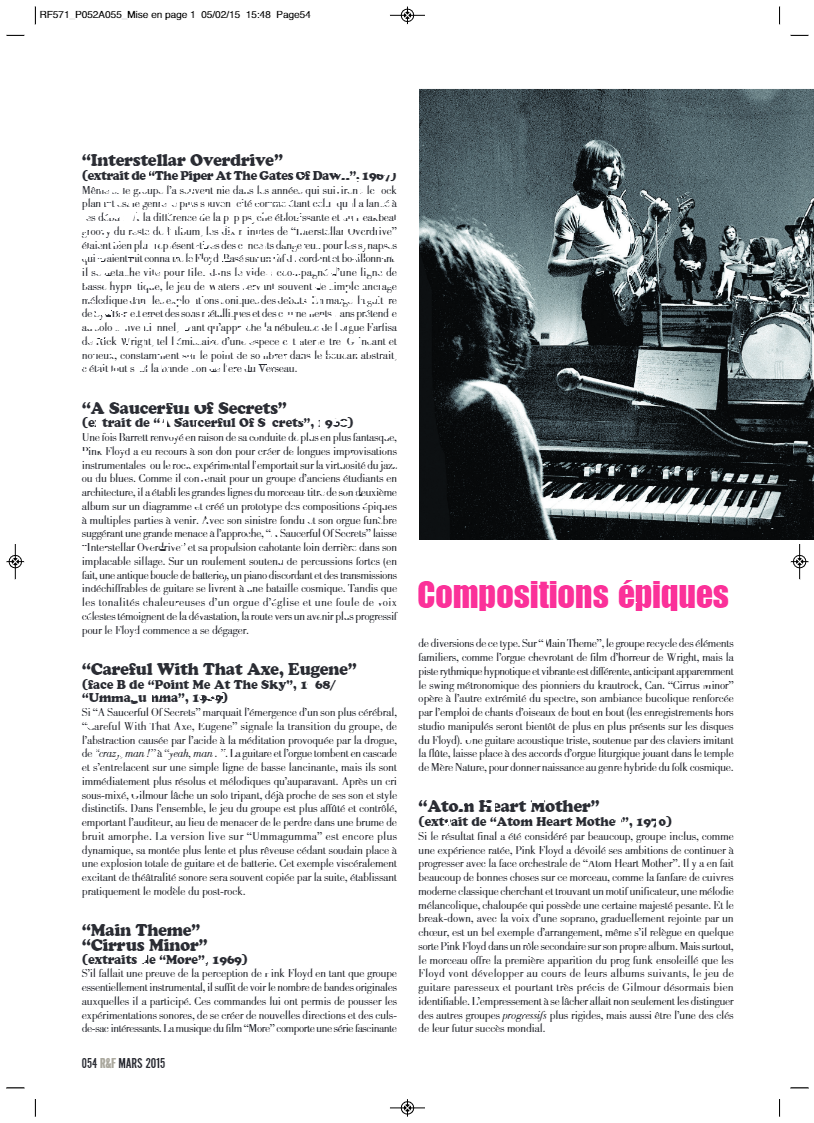

“Main Theme” and “Cirrus Minor” (from ‘More’, 1969)

If proof were needed of the Floyd’s perception as essentially an instrumental band, you only need to look at the amount of soundtrack work they attracted. These commissions allowed them to stretch out and experiment even more with their sound, creating both new directions and intriguing cul-de-sacs. Their soundtrack to the film ‘More’ features a fascinating series of such diversions. The “Main Theme” sees them recycling familiar elements such as Wright’s horrorshow organ, but it’s the pulsing, hypnotic rhythm track that’s different, apparently anticipating the metronomic swing of Krautrock pioneers Can.

“Cirrus Minor” operates at the other end of the sound spectrum, its gentle bucolic vibe enhanced by the use of birdsong throughout (manipulated field recordings would begin to feature increasingly in Floyd’s work). Sad-eyed acoustic guitar and flute-like keys dissolve into pure, liturgical organ chords, a mass in the temple of Mother Nature, birthing the hybrid genre of cosmic folk.

“Atom Heart Mother” (from ‘Atom Heart Mother’, 1970)

Though the final result was viewed by many, including the band, as a failed experiment, Floyd made plain their ambitions to keep progressing with the side-long orchestral rock of “Atom Heart Mother”. In fact, there’s a lot that’s great about the piece, such as the opening modern classical fanfare of brass searching for a unifying theme, and then finding it, a rolling, melancholic melody that possesses a certain lumbering majesty. And the breakdown to the voice of a lone female soprano, gradually joined by a full choir, is a nice piece of arrangement, even if it does somewhat relegate Floyd to backing band on their own record. But most importantly, the track features the first appearance of the sun-kissed prog funk that Floyd would develop over the next few albums, Gilmour’s lazy yet pinpoint-precise guitar style now clearly recognisable. This willingness to loosen up and stretch out would not only mark them out from other more rigidly ‘progressive’ bands, but also be one of the keys to their future global success.

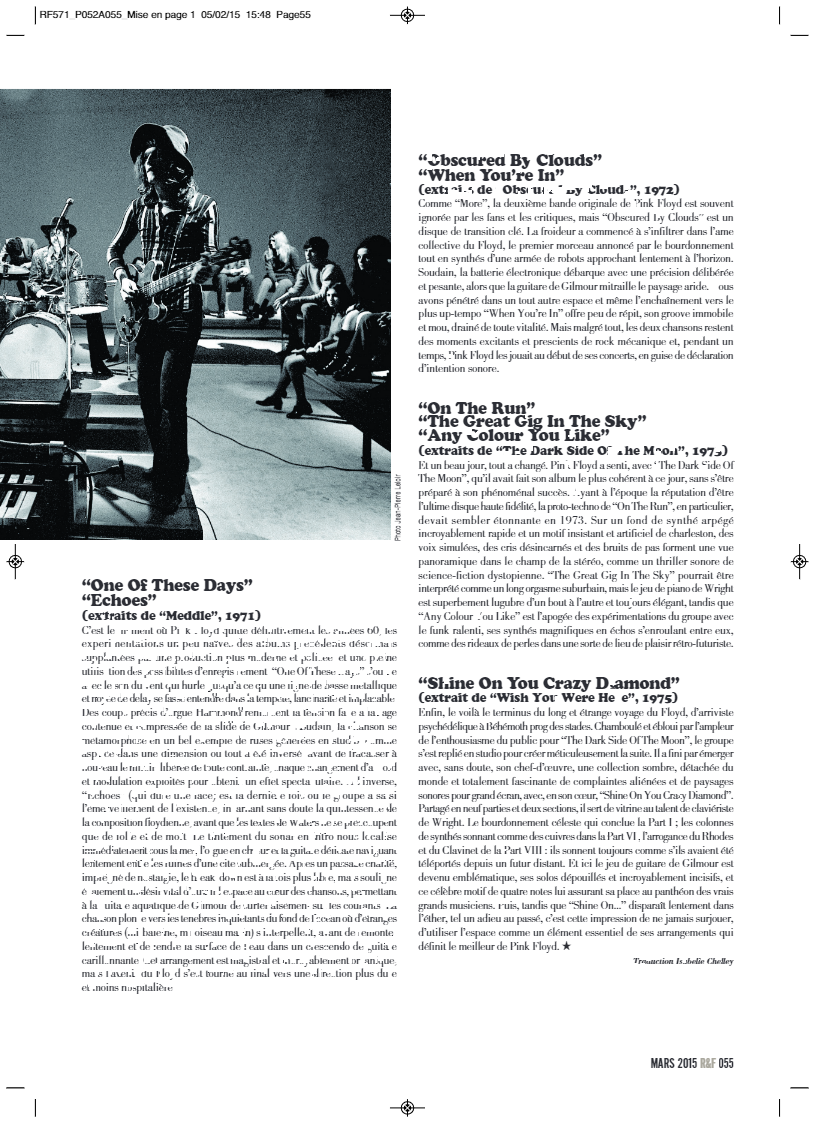

“One Of These Days” and “Echoes” (from ‘Meddle’, 1971)

This is the point at which Floyd definitively leave the 60s behind, the sometimes naive experiments of previous albums now superseded by a more modern, technological production sheen and a real embrace of the possibilities of the recording process. “One Of These Days” begins with the sound of howling wind before that pulsating, delay-drenched metallic bass line cuts through the storm, driving and relentless. Precise stabs of Hammond organ ratchet up the tension against the crushed, constrained anger of Gilmour’s slide guitar. The song suddenly turns itself inside out in a still impressive piece of studio trickery, as though sucked into a negative dimension where everything’s reversed, before smashing back through the mirror, freed from all restraint, every chord change and modulation milked for dramatic effect.

In contrast, the side-long “Echoes” is the last time the band would be inspired to capture the wide-eyed wonder of existence, and is perhaps the quintessential Floyd composition before Waters’ lyrical preoccupations with insanity, alienation and death descended upon them. The opening sonar ping immediately locates us under the sea, the chorused organ and delicate guitar slowly navigating the ruins of a submerged city. After a vocal section suffused with nostalgia, the funky breakdown is not only looser, but also emphasises a vital willingness to open up space within songs, allowing Gilmour’s aquatic guitar to effortlessly surf the currents. The song dives down to the eerie gloom of the ocean floor, where strange creatures – half-whale, half-seabird – call to each other, before slowly ascending and breaking the water’s surface in a crescendo of chiming guitar. It’s a masterful and incredibly organic arrangement, but Floyd’s future ultimately lay in a harder, less hospitable direction.

“Obscured By Clouds”/”When You’re In” (from ‘Obscured By Clouds’, 1972)

Like ‘More’, Floyd’s second soundtrack album is often overlooked by fans and critics alike, but ‘Obscured By Clouds’ is a key transitional record. A coldness has started to creep into Floyd’s collective soul, the opening title track heralded by the synth-heavy drone of a robot army slowly approaching over the horizon. Then wumph! – the electronic drums kick in with a deliberate, leaden precision while Gilmour’s guitar strafes the barren landscape like a searchlight. We’ve entered a different headspace altogether, and even the segue into the more up tempo “When You’re In” offers little respite, its locked-down, enervated groove drained of all vitality. But for all that, both songs are still thrilling, prescient slabs of mechanical rock, and for a while, Floyd even opened their concerts with them as a sonic statement of things to come.

“On The Run”, “The Great Gig In The Sky” and “Any Colour You Like” (from ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’, 1973)

And then everything changed. Floyd felt they’d made their most cohesive album to date with ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’, but were unprepared for its phenomenal success. With a reputation at the time for being the ultimate hi-fi record, the proto-techno of “On The Run” in particular must have sounded astonishing in 1973. Against a backdrop of impossibly fast arpeggiated synth and an insistent, artificial hi-hat pattern, mocking voices, disembodied screams and desperate footsteps are panned around the stereo field like a dystopian sci-fi thriller in sound.

“The Great Gig In The Sky” could be interpreted as one long suburban orgasm, but Wright’s piano playing is beguilingly tender throughout and never crass, while “Any Colour You Like” is the apogee of Floyd’s experiments with slo-mo funk, its gorgeous, echoing synths coiling around each other like beaded curtains in some retro-futuristic pleasuredome.

“Shine On You Crazy Diamond” (from ‘Wish You Were Here’, 1975)

Then here it is, the terminus point on Floyd’s long, strange journey from psychedelic upstarts to stadium prog behemoth. Dazed and confused by the scale of the public’s enthusiasm for ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’, the band retreated to the studio to painstakingly create its follow-up. What they eventually emerged with is arguably their masterpiece, a bleak, otherworldly but utterly compelling collection of alienated laments and wide-screen soundscapes, with “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” at its heart. Split into nine parts and two sections, it’s a showcase for Wright’s keyboard talents: the heavenly drone that part 1 fades up with; the horn-like towers of synth in part 6; the strutting Rhodes and Clavinet of part 8 – they all still sound like they’re being beamed in from some distant point in the future. And Gilmour’s guitar work here has become iconic, his spare, painfully sharp solos and that famous four note motif guaranteeing his place in the pantheon of truly great players. As “Shine On…” slowly disappears into the ether like a valediction to the past, it’s that sense of never over-playing, of using space as a crucial part of their arrangements, that defines Floyd at their very best.